|

|

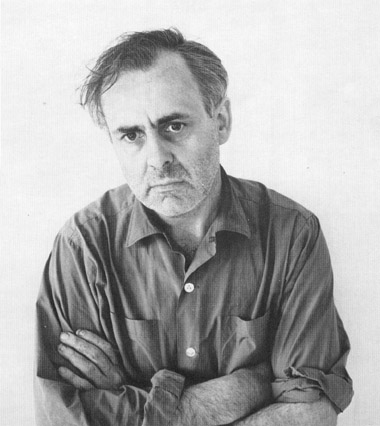

Reflections: November 3, 1980 I sometimes wonder why I feel a compatibility to street scrap. I've thought about it, and I remember my trips to the city dump when I was a kid. Those were spectacular things.I used to go with my dad. There was always a man there with a badge on who would direct the people and say where to dump the garbage. He would pull the good pieces out and put them in his shack. It looked like that was the greatest thing. When I was a young kid and people would say 'What are you going to do when you grow up?' And I would say 'I want to run the Salt Street Dump.' So while other people wanted to be doctors and lawyers, I really wanted to have that job and have first shot at all that stuff. It could be there are a lot of things that get a person looking down at the ground. It could be I was just round shouldered. I don't know. It seemed as though it was always here. I was born in 1919 in Saginaw, Michigan, and grew up in a family of inventors, machinists. I somehow knew that there was something outside the machine shop. I didn't know what kind of thing. So when I got to the University of Michigan I enrolled in architecture. I noticed that everybody seemed happier one floor down. I went down there and found that was the art and design school. So I quickly transferred into that. But I was always split. My admiration was for the people that called themselves serious artists, fine artists or whatever they called themselves, because I was a product of the Depression and I really respected the person who had the courage to say 'I won't be able to earn a living but I'm gonna do what I want to do.' I was in the design program, but somehow the people that I really looked up to were in the other program, so I was kind of a split person from way back there. Some time later I realized that my choice wasn't all wrong. I noticed that most of the fine arts majors ended up as commercial artists. They were won over by General Motors and the agencies and so forth. And somehow a few of us who were designers persisted in doing fine arts or serious stuff So it worked out all right. But the idea of trying to lead a double life seemed almost inevitable from the beginning. I went to the University

of Michigan from '38 to '42. The whole area of design was just opening

up from a rather classical world. The foundations of all the classical

traditions were being broken. They'd been broken from the turn of the century,

but they were broken in such remote ways; it wasn't mainstream. You'd

find it in books, it was all there, but nobody ever saw it. And so it was

this way in design, it was the same way in architecture, it was the same

way in everything. It took very little doing to accomplish, we'll say,

the design of a chair or a table, a book or whatever, that was outstanding,

because the world was basically flat. If you were young and you had some

concepts, you could play these many games. So, I got off into

all these things and it was great because you felt like you were carrying

the world on your shoulders, going to change the world and all that.

It was really fun.

|

|

|

At the time that World War II broke out I was finishing up at the University of Michigan. Because I was from an engineering background, I associated myself with the engineering school students. The government needed engineering type people for the development of tanks and missiles and ordnance materials, so they were taking people within college groups and giving them special training. They sent me over to Chrysler Tank Arsenal three weeks before graduation so I graduated after I was in the Navy, perhaps a year later than I should have. The Hudson Motor Car Company had a naval arsenal and they were making gun directors for ships. Anti aircraft guns. I worked there for awhile on tools and gauges and stuff. And then I went into the Navy and spent a couple of years as an enlisted man, and a couple of years as an officer. And then I got out and shut that whole thing out. I can't remember too much about it. I hated it. I came immediately to Chicago when I was released from the Great Lakes, came right here and went back to school at the Institute of Design, Moholy Nagy's school. I had studied during the war just a little while with him. I was stationed in Chicago for a time and I enrolled in school. And then when the war was over I ran right back. I went through the whole program. Then I started to work here in Chicago as a designer. I was asked to teach. I taught at the Institute of Design for three or four years and then left the Institute to go to Navy Pier. See, the Institute of Design had kind of gone into a decay. It had been taken over by IIT and Jay Doblin was hired to direct the school. It was being reoriented into a less philosophical school, a more industry oriented school. And so many of us found it convenient to go to the Pier. John Walley had already begun the process of building a design school there, although at that time it could hardly be called a design school. But he envisioned it. And so a number of us joined him with the idea that this would be the real school. The one that was being destroyed would be rebuilt as far as possible. What we didn't realize was that a university, by obligation, cannot take on the extreme positions that some of us would have liked to have taken. I think the university process is one of trying to be fair and equal, to try to represent all concerns, all approaches to everything. What happened is that as the school grew it probably became more diffuse and when it finally burgeoned out into the Circle, why it was totally diffuse. So we have now a university type of school, not a bad school by any means but certainly not the kind of a school that one might envision as being a spearhead of some sort. It was very hard to do that within a university. I always visualized teaching being a little bit like helping a baby to learn to walk. You help him and pretty soon he can not only walk, but he can run faster, he can come up and give you a kick or he can knock you down and run. He can outperform you. And I wondered whether I would be able to teach because teaching is really giving. Giving, giving, giving. There is receiving too, but you're not much of a teacher unless you really want to give a lot. I began teaching reluctantly, but found that you can't help natural things in the world to want to help. There's nothing more satisfying than to know that somehow you've helped somebody. Then there's a very difficult feeling when you know that you haven't helped somebody, which is the other end of the thing. And you get them both. There are a lot of uneasy feelings about teaching because you can never be good for all of them so there's a lot of frustration. What could I have done that I didn't do? But I gradually have been able to accept the idea that I get through to some, somebody else will get through to someone I don't get through to, and somehow it'll all work itself out. Probably my favorite class is the earliest fundamentals class, which is foundation, and the earliest communications class, which is transition. I like them best because I think that if you get a person started right you can't stop them. At the top levels you don't really have the same opportunity to touch people. They develop their immunities by the time they get to the top. If the average life is one

where values are intellectual values, it is so easy to grow into a world

which is teaching you to use seeing as identifying. Learning to read, learning

to cross the street without getting hit by a vehicle. Learning to identify

the cat and dog and the letter A and B, learning to identify through seeing,

is so much a process of growing up that it's quite possible to grow up

and not be able to see other than to identify. A kid can see, but when

you work at a kid long enough, to teach him how to read and write and cross

the street, at a certain point you almost have to help him again to be

able to see what he could see when he was little. And so to that extent

it is not unexpected that a person may become adult and not see some of

the important aspects of art. If there's another thing that I'm concerned

about, it probably would be to help a person to see that there is more

to the profession than turning out (underlined passage is interpolation

in tape gap) a handsome brochure or a beautiful hubcap for an automobile.

I think that I represent a small resistance not resistance, clarification

for some students that success isn't just dollars.

|

|

|

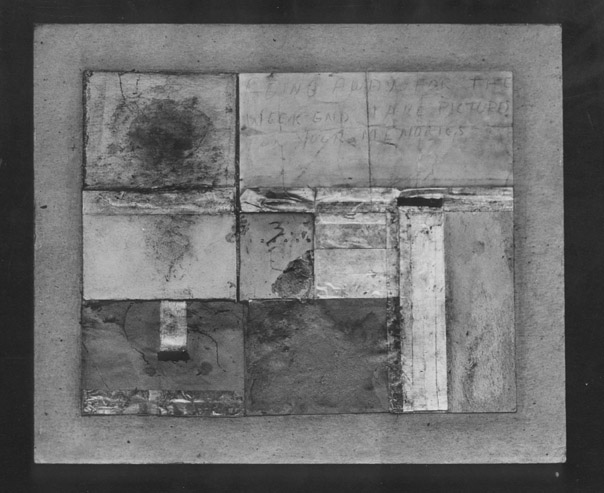

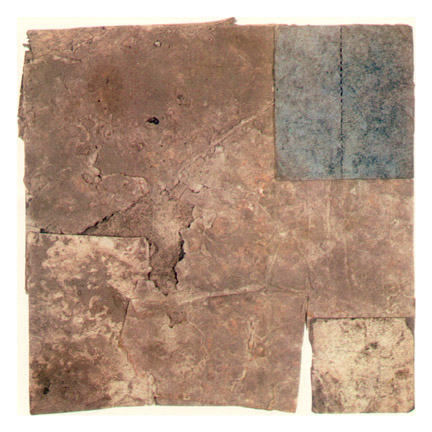

Teaching has helped me. A girl called who's teaching in Washington State now who had been a student of mine. She called yesterday and said that she wanted me to know that she's a teacher and that she was having such a good time because she was learning so much by having to clarify for herself in order to teach. And how she was finding that the things that I had done to her worked so well on her groups and so on. She just had to call me and tell me, 'Well, this is a great way to live and I owe you a lot.' I think that teaching is a clarification process, that when you feel something you don't necessarily understand what you feel, or when you can do something you don't necessarily know how you do it. And when you teach it you have to begin to try to dissect and understand some of the processes which are rather complicated. I say to students 'Some day you have to teach. If teaching has been good for you, then turn around and some time do it for somebody else, whether you teach in a classroom or whatever. Repay it.' I believe that this is true. I never intended to teach. I was urged to teach at the Institute of Design and I said 'No, I'm not ready,' and they said you never will be ready, so start to teach. I certainly am such a shy person that it's very hard for me to confront a group of more than a few. Teaching was not what I looked forward to. I'm 61 now, I have to think about that. It's a pretty terrifying thing to have no excuse for not being really good. And teaching is a good excuse for not being really good, because you can say 'Well, it's taken me away from my work.' If I can't hit a high, then it isn't worth much doing things. At one point in my life I could hit highs in a lot of things at least they felt like highs because it was an early growth period. It's always easy at first. But then at a certain point I realized that I was kidding myself and so I had to start narrowing down. At this point I probably am far less concerned about the design of an annual report or a brochure. A book interests me but there are so many things that I find so thin. I faded myself into designing for not for profit organizations for a number of years at the and. Now I design for myself. That's about it. You only have so many hours and so many years. When you start counting them, which I'm afraid I am, then you become more directed and more selfish. I see graphic design sort of like design for the garbage can, for five minutes' duration, and my ego is getting to be too big. I want to make it last for at least five or ten years. I think it's important in looking at somebody's art to see where he came from or where she came from in terms of continuity. I don't think you can judge a person by any one work. I don't think you can judge a person by what he's done in any one year. You can judge his potential, but as far as actually understanding the whole, the meaning, I think you have to see continuity. I've been working on almost the same kinds of collages that I'm working on now since '46, when I got out of the Navy. I was studying at the Institute of Design and became involved in collage. I then became a designer working in consultant design kind of processes, which are so removed from reality in some ways slickness that I found that the slicker I was, or was expected to be, the more important it was that I could counteract it, antidote it, with something unslick. So that I think in some measure the materials I use are a reaction to something. At this point I'm finding myself cleaning some of my stuff up, because I think I'm removed enough from that clean world of pinstriped suits and acetate overlays that I can think a little bit differently. I pick up material, street stuff,

that isn't too wonderful but it's kind of nice. I feel like I'm picking

up brushstrokes rather than artifacts. And I build with it. By a kind

of trial and error process I find friendships between materials. I tried

to think about it one time and it seems as though it's a kind of an

exchange process where I am in control some of the time and some of

the time it's controlling me. I would feel bad if I ever yielded

control but to yield some of the time I don't mind. I suppose

it would be grand if everything came straight out of my gut. This is

why I admire a painter who can attack a zero, neutral condition and

perform. This takes something very special; either naivete about

good and bad so he isn't hurt while he's doing it, or a sense of backup

experiences which will allow him to move forward. But to me a blank

canvas would be a most terrifying thing unless I had a plan.

|

|

|

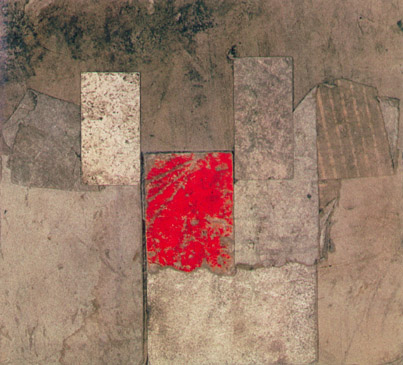

And so for me collage becomes a planning process. It probably relates to the fact that I'm design oriented. I probably was a designer because of certain capacities or lacks of capacity. I've said to people that I feel as though collage fits me because I can make a mistake and can retract the mistake, I can compare and so forth, which is very hard to do in painting. There are ways a person can retract a painting too; it's not that all painting comes out, painted with the mind shut off. But a painting, generally speaking, is a different process. My work isn't stable. A person with a real sense of accomplishment probably wouldn't worry about whether it will last 500 years or 1000 years. I see some of my stuff holding up for 30 years but I don't know if it goes any farther than that. And some of it doesn't hold up that long because it's all unstable material. It's found material. I'm leaving my pieces up to other people to eventually deacidify, and that may or may not happen. I should be deacidifying the paper so that it will not crystallize, not break up. And I will eventually. When I grow up. No, I'm just going straight away and saying the hell with what happens to them. But it's a kind of incongruous thing: a stainless steel frame around a little piece of Kleenex that has some vegetable dye in it. Something's a little goofy. I guess that the more common place or unacceptable materials that one might use are, the more important it is that they be given special consideration or they'll be ignored, because that's pretty much what the world is made of. And I also know that a thing that's not smooth doesn't enjoy a world which is rough or rougher. It does enjoy a world which is more anonymous, contrasting. If I had to name two visual influences, I'd have to say Mondrian, because of his pure space sensitivity ,and then I would have to touch Paul Klee, who I feel is so right and personal and searching in a completely different way. I've always seen myself as being a humble admirer of these two extremes, knowing that I probably don't belong at either end. If you like both of them as much as I do you don't belong in either place. There's some kind of connective. But I feel those two presences very strongly. And I feel very strongly towards Van Gogh for another characteristic which isn't so much a visual one. I read his letters one time and I was touched all the way; I guess I identify with his difficulty, not in surviving, because that hasn't been my problem; but everything he achieved was hard work. I've always had to fight to make anything happen. It's been a battle. And I sense in Van Gogh there's a terrific battle just to make an inch of progress. So I guess it's a sympathy or a kinship of some kind. I respond to the softness of Klee. Klee is remarkably tender, fragile. The subtleties . . . I have a Paul Klee painting that I bought many years ago, and I used to sit and look at that thing. He would cross lines and you'd look very closely and see that he'd worked so carefully to reduce the cross by lightening it out. Most people are looking at the big thing, but he was seeing the little, most subtle aspects. Or he could put two colors or two shapes together that were so personal, so subtle or so unexpected. Whereas Mondrian was completely committed to something so pure. I do have a good space sense.

I had to rely on something that did not require facility, which space could

be, and form. So that has been my strength. But the other aspect,

the quality of softness and so forth I'm sure makes the kind of collage

I do important for me.

|

|

|

I keep trying to make prints. It always seemed to me that Mondrian said it so well I'd like to make something so simple that it could be printed in the morning paper and everybody would have one. I think the idea of art being precious is dumb. Now here is a print: my boy died of cancer a year and a half ago and we buried him under an apple tree and I made this. I was making this the day before we were planting the tree. He said 'Bury me under an apple tree and eat the apples and I'll be alive with you.' So I was working on this and I didn't even know what happened and this (what) fell on there, so I knew that the print was for him. I guess I know what art shouldn't be. Maybe I don't know what art should be but I know what art shouldn't be. Art shouldn't be a symbol of success for people that have a lot of money. To acquire it, to be able to say 'Look, I have a this or a that', this to me is pretty terrible. Art should be an experience for the person who has made it. And presumably there are people to whom it would be a rewarding experience just to see it. But this business of collecting and possessing is hard for me to quite understand . I'm not saying that all collectors are collecting for poor reasons. It isn't true of some. There are people who buy what they really feel doesn't matter what the name is and so forth. Then there are people who are buying as patrons and perhaps this is again a legitimate kind of a thing. That's probably all right. But I think there's a lot of questionable art collecting . I do feel though that Chicago is good for an artist, or I used to think that Chicago was good for an artist because they left him alone, or they left her alone. It seems like artists would go to New York because there was an existing pattern of being discovered, being promoted, being taken care of and so forth. And that was a good reason for people to go there. But for the persons who wanted to be left alone, this was a good place. They left you alone. For me this has been fine. This is why I hesitate even to do an interview. I'm giving up just a little bit more of the privacy that to me means so very much. And every time I give away a little it's gone. So I think that Chicago's been great in that I could be whatever I am without great pressure. Nobody cared, and that was good. I can't say that Chicago is that way as much now as it was then. I find suddenly people are concerned about me and I'm wondering if it might be time now to go somewhere else. But there's a real contradiction there because I don't make things and hide them, I don't make things and burn them. I make things and hold them up and say 'Look at them'. And I put my name on them. I don't sign them John Doe or anything like that. I stick my picture on the back. I want nobody around when I make a picture. I'm not a public performer. But if I make something that I believe is good, I can't deny that I'm pleased if somebody says 'Gee, I think that's good.' On the other hand I abhor stupid openings and things where people run around and say 'Aren't you grand!' And I know that they don't even know what they're saying or what they're seeing. But once in a while I think we all need a little applause even though we wonder whether it's genuine or not. I think that it's disturbing that the world of art has so many promotional problems built into it, that the artist sometimes survives if he's a promoter or the right kind of personality, a showman or whatever. The great numbers of people that are in art is healthy and good. The competition is not a bad thing But when a person almost has to be a public relations personality in order to survive then it's not quite so good. A friend of mine who left Chicago for New York was saying how when he first went to New York a number of years ago, it didn't matter what kind of place you lived in, but some time during the year somebody would be knocking on the old door: "Hello, I'm from such and such gallery or museum and just thought I'd stop in. Somebody said that you're doing some interesting work." And he said that happened for a number of years in New York. But he said in recent years, the situation has become such that you had to go to them. They don't come to you any more. And he, being a very shy guy and very good sits there and works and works and nobody sees his work because he's too proud or too shy or too something to go out and promote. He said that the Institute of Design he came out of the Institute of Design would be proud of all the artists here in New York. He said that they have a five year plan and they have charts, where they want to be and go, and what gallery they want to show in. They measure the gallery and they check out the audience and they analyze, they almost compute. They build work to fit the gallery. they work the gallery owners. It would be absolutely terrible,

he said, except that they're also good artists. Which is kind of interesting

because what it comes down to now is, I guess, the necessity to be more

than an artist to be an artist.

|

|

|

But I have to admit that I almost feel a guilt once in a while that I'm given more attention than I really think is appropriate. I look around and I see persons who are very deserving of attention because they really committed themselves with every bit of equal integrity, who are overlooked. So I begin to see the circumstance, the chance factors that are involved in being "accepted" or whatever you call it. So I see the process as being one where I get a break sometimes and while it may feel good, I know that it doesn't mean all that much. It means that I was standing at the right place at the right time and the right person walked along or something. Sometimes not much more than that. I would hope that it isn't all chance but chance is such a big factor. It's certainly pretty hard to feel secure and accomplished just because somebody happens to say 'This is it, this is good.' I'd like to see what it would feel like to have several consecutive years that were hard running productive years, without the complications of school, without the complications of the stress of divorce. Because I know that if a person is splintered a year doesn't mean very much. But a year can mean so much if it can be one of concentration. That would be true in anything, writing or whatever. I had too many children, too many problems, to ever get a sustained year to year to year thing. It's been sporadic. I had a sabbatical a few years ago, it was great. It was free of stress. It was like five years or more. I simply accomplished so much much more than I ever do during a normal year. I'm caught in a situation

where I thought life was forever and I decided I was going to be a designer,

an artist; not just an ordinary designer but a product designer and a graphics

designer, an architectural designer, the whole thing. And I'm not just

going to be an artist my gosh, why just be a painter? why not be

a painter and a sculptor and whatever else? And why not teach at the same

time and raise seven kids and all that kind of stuff? But at a certain

point your hair gets gray and your knees begin to buckle a little and you

say 'What am I doing? 'It's great if I could live forever.'

|